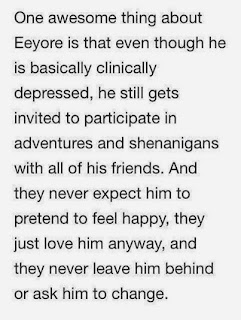

“Understanding love from only one religious doctrine - like understanding God - usually sets us up against each other. It's only when we free ourselves from the shadows of limited thinking will love be the bridge across differing viewpoints, and not the cause of them.”

— Mickie Kent

A good friend called me the other day. She was uncharacteristically grim. "When I look at the news headlines, I just despair," she said. "It's all so dark in the world." And she is right. Our climates are in upheaval, our living costs rising, our communities feel fractured - and with stories of public disasters the mainstay of headlines, we've lost trust in our police, the politicians and even the people that print the news. Not surprising, some would say, when it seems that our society has been built to accommodate the "lucky few" of the population, while the majority carry the burden of making society work.

But the dark shadows that loom over us are long ones. It stretches back down the ages to when we began living in societies that pushed for dominance. And there are very large chapters in our history that still haven't been properly addressed. When we look at war torn places like Iraq and Afghanistan, and what the creation of borders can do to people, it sometimes feels like we haven't learnt anything from two world wars. There was a time battles were fought only by soldiers, but now everyone is a target - men, women AND children. And the traumatic impacts of each war humanity fought has lingered, helping to make us who we are.

Just recently the UN Special Rapporteur on occupied Palestine accused Israeli authorities of conducting colonialist policies that constitute forms of apartheid and ethnic cleansing in the occupied territories in the West Bank and East Jerusalem, as Oscar-winning actress Angelina Jolie and British Foreign Secretary William Hague visited Bosnia to promote a campaign to end sexual violence against women in war. In a very real sense, as the spiritual descendants of war victims, we are all suffering from post-traumatic stress.

And soldiers suffer mental breakdown, too. The news is filled with recruits being charged with explosives and terrorism offences, going on mass killing sprees in their own encampments, or killing civilians during drug-fuelled sadomasochistic sex sessions. But it's the good that stand out in any conflict, and we must not forget that the majority of those who served in Afghanistan, and Iraq, will be paying the true cost of war for decades to come, the physically incapacitated and the mentally injured, along with the families of the dead.

In the nations they have fought for, many believe that these returning soldiers should be considered national heroes for the conduct and courage they have shown in wars they really should never have been in, while it's the government and politicians who argued the case for war who should bow their heads in shame. Yet, for all of us, it's a nightmare from which we just can't seem to wake up.

However we need to break from our stupor, because although it would be convenient to try and imagine such things never happen, it isn't feasible in the long run. If we truly wish to invent a better history for ourselves, we have to change our perspective - and in doing so, rather than seeing things as being wholly bad, reinterpret them as actually being another chasm to cross, or another step in life's surprising journey.

Great minds have pondered that as there can be no East without West, so there can be no good without bad. Those who want (or expect) an extant state made up entirely of good don't understand that good can only be relative and not absolute. Without an opposite to be compared to, it can't exist they say. Others, though, believe that bad is a negation of good, rather than a purpose for it - but I believe that either way the wrongs committed only negate goodness if we allow them to fall on fertile ground.

Every Palestinian who has suffered at the hands of the Israeli armed forces, every Bosnian who has suffered at the hands of the Serbs has the chance to turn death into a fighting chance to reconcile, and to live. Because in the face of its truth, especially at our end, there is little to distinguish us, Jew or gentile. We can't escape the truth that the world is only as good as the people in it, but then, so, too, is it true that the world always looks worse than it is.

And as sure as we live and die, love MUST have its chance in between. Because if the love within your mind is lost, if you continue to see other beings as enemies, then no matter how much education or knowledge you have, no matter how much material progress is made, only suffering and confusion will ensue. Furthermore, it reads like cosmic irony to say human beings wish to control everything but the violence they have inbred into themselves.

Regardless of how we have subverted our true nature, love shows us that it's not about control at all. It's just about being and allowing every other living thing to be, too. Today we are reaping the poisoned fruits from the seeds of bloodshed sown in a long history of war, but by getting back on track with love, we can come out from under the long, generational shadows cast by its dark clouds, and avert many of the very real crises of global conflict afflicting us today.

We must also keep in mind that these are times of changing definitions, and conflicts will arise because often defining something is not synonymous with understanding it - especially if we try to categorise people and beliefs. Definitions can limit as much as they explain in such cases, when what is first and foremost necessary is understanding.

Understanding the shadows of the past

Understanding will always come from within. If people are rude and inconsiderate, then often there will be a reason for it. If someone is rude without reason, we usually suspect a failing in their mental faculties. If a kitten doesn't encounter a human in a friendly context between the ages of three to eight weeks, it is more liable to go feral - and we are not much different. It's only the truly courageous that seek to be caring in the face of mistreatment time and again. This doesn't mean, however, that they are glutton for punishment. It means they have discovered that if they allow their own caring nature to be corrupted by the mistakes of others, then they will have been defined by another's actions, and not their own.

This is why when we consciously choose to pursue a career doing what we love, we often break with our own stereotypes in order to do it. For example, if a woman's passion is motivational speaking and she wants to become a public speaker, there are many definitions she needs to break in her own mind, as well as that of her audience. Historians point to ancient Greek thought and what is said to be the beginning of Western literature, where from the outset women are told they cannot speak with the voice of authority.

Pertinent to this issue, art historian Mary Beard spoke on the public voice of women, as part of the London Review of Books Winter lecture series recorded at the British Museum. In a talk titled "Oh Do Shut Up Dear!", Beard explored how, from torn-out tongues to internet trolls, women's voices have been silenced in the public sphere throughout the history of Western culture. Women risked a backlash exposing their voice in ancient Greece as they do exposing their breasts to breastfeed in public today.

Using examples ranging from Homer's Odyssey to contemporary politics, and from the writings of Henry James to threatening posts on Twitter, Beard argued that public speaking has all too often been regarded as "men's business" and that commonly held attitudes to the voice of authority need to be readdressed and reappraised. Her argument highlighted how this Homeric moment has pervaded the nature of communication between male and female, and indeed, what we consider to be male or female communication - where men hold authoritative "muthos" as opposed to the chatter or gossip of women, or "mythos", from which the word "myth" is derived.

Obviously Western culture does not owe everything (good or bad) to the Greeks or the Romans, in speech or anything else. Newly uncovered discoveries have formed the understanding that the ancient Greeks weren't great original thinkers at the best of times - most of their thinking was taken from somewhere else, such as the ancient Semitic civilization of Phoenicia, or the Assyrians and even further back to the Sumerians. It's a pity the ancient Greeks didn't adopt the Sumerian way of treating women as equals, but some historians now treat the ancient Greeks as simply passionate documenters whose historical text has had a good survival rate (thanks in large part to its assimilation into the ancient Roman Empire).

And to be honest, thank heavens our culture doesn't owe everything to that classical way of thinking. As Mary Beard said, even a classicist - or especially a classicist - would not fancy living in a Greco-Roman world. Our political system has happily overthrown many of the gendered certainties of antiquity, most obviously - if only formally - equal political rights for women. It's a reminder though that the "fairer sex" haven't had it fair at all, battling hard with the myths and stereotypes attached to their gender to break into the "boy-biased" areas of life with their own contributions, and gain equal recognition for their efforts.

A shining example is pioneering developmental psychologist Professor Uta Frith, whose lifetime study of people with autism has transformed our understanding of this mysterious condition. In a film by Horizon for the BBC, her contributions show how people with autism perceive the world and interact with their surroundings, and how, for them, another kind of reality exists, and that many of us could be just a little bit autistic, too. You could say that it was her "motherly instincts" which attracted her to this particular field, because of the autistic children she first encountered. Passionately wanting to know more about them inspired her to dedicate the rest of her career to studying the autistic mind. But her efforts have benefited man, woman and child alike.

If clarification were needed, women's voices have always been raised in cause for women's issues - even in antiquity, if not consistently - but their voice has never spoken for the whole community, as it can do so now. Today they can speak up not just for women, but for men, too, and for all living things. It is no longer niched into their own gender.

Yet, we still lie very much in the shadow of the classical world. For although the voice of women may today carry just as much authority as a man's in Western societies - America is an exception, still locked in her Greek classical cage. This is true, even though - conversely - it has been the voice of the American woman that has been heard the most throughout the wider world, especially when it comes to global issues, possibly because their country has helped cause many of them.

And although we are under the shadows of our past, Beard is not saying we're simply the victim of classical inheritance, or that the ancient world was merely misogynistic as a rule. But those classic patriarchal, violent traditions have provided us with - and continue to provide us with - a template for thinking and how to deal with things. In Britain, for example, our identities were forged by the ancient Romans when they built Hadrian's Wall, forcing a middle land of peoples into a north-south divide when they belonged to neither. The border legacy has remained, however, with the issue of Scottish independence from the United Kingdom still alive and kicking.

Along with historical borders, gender is obviously a part of that identity mix, but so, too, is how we treat the vulnerable and the meek. Should we put our weak babies out into the wild to die of starvation as the Spartans did? Thankfully the majority of us would be horrified at that, but as historians we can see classical themes being replayed and re-emerging all across the 20th Century, and we are witnessing its death throes in the second decade of the 21st Century.

What the future will bring

Death throes or not, we have yet to discard this traditional package of views that goes back two millennia. It still underlies our assumptions towards each other. We continue to trivialise people we see as weaker. Women who stand up for themselves are whiners we say, while men who stand up for themselves are winners. We are still trying to learn how to connote authority to love, and to peace, and to wisdom that speaks, rather than the obvious roar of the charging brave. That has its place too, no doubt, but so does a consoling whisper - be it from a man or woman.

These problems are not hard-wired into our brains, but hard-wired into our culture, our language, our way of talking about different opinions and people and into the millennia of our history. Lest we forget, women are not the only groups in our culture who are, or feel themselves to be voiceless. And having these minorities ape the majority to have their say may be a quick fix, but not the long term solution. It's just a transference of power, rather than a shift in understanding.

Likewise a powerful Palestine would probably act no different than Israel, and the criticisms aimed at America can also be made of Russia, China and even India. We need to start hearing differently, speaking differently, and thinking differently. We need to rethink our governing principles to encourage communication that can transcend the classical voice of violence. It won't necessarily guarantee us a better future, because there are no guarantees in life, but it will at least be a change from the old one.

All futures are ones that "might be", but often they are not new worlds - simply an extension of what began in the old one. If we continue to pattern ourselves after every dictator who has ever planted a dirty boot on the pages of history since the beginning of human acknowledgement then what else can we expect, but more of the same? Obviously such a future will have refinements, technological upgrades and a more sophisticated approach to the destruction of human freedom, but like every domineering society that preceded it, our future will stick to one iron rule: that any opposing logic is an enemy and truth is a menace.

Nevertheless, such a future is also destined to fail in time. Any state or belief or ideology that fails to recognise the worth the dignity of all life renders, is itself obsolete by default. And this is the most disheartening truth of all: that it's we humans that continue to keep alive a self-destructive philosophy by transference every millennia or so. We are not only the victims, but the creators of this vicious cycle that serves no one.

As humans we are built out of flesh, but we also have a mind that can overcome the adversity of that flesh - and stop what was previously planned to happen. But that requires an extraordinary consciousness, not solely personal but global, too, for until we are all connected with our soul, a human being can be endowed with a divine mind and yet be separate from it. Our human history is a prime example of this. The culture that gave us Aristotle, also gave us many of the schisms that Western thinking finds itself battling with today.

And as those ancients did before us, we are misguided to think we need violence as the drive in our genes to take us towards the pinnacle of truth, like a car needs speed to move forward. But neither life, nor the religion that instils subservience to its violent doctrines, is akin to a car that can reliably take you anywhere. Yet, zealots will tell us to go on "blind faith" - on petrol made out of thin air - not realising that it's such idiocy that helps to subvert, and thus stall, the mind.

Faith should help make us more self-aware, not blind us to the truth out there. If holy books are indeed a sat-nav to help guide us through life, then it needs to be open to the ever changing nature of life. Rather than a guide that spews out stories about a god who keeps bouncers at Heaven's gates to keep out people irrespective of their quality of goodness - such as same-sex couples, the suicidal and whoever else doesn't fit within the confines of a narrow mind - we need a better guide to steer us out of the shadows that still hang over us today.

And merely swapping one religious doctrine for another is again just a transference of power, rather than a shift in understanding. There are some that will argue Judaism is no better than Christianity, and Islam is just an extension of the two, while Buddhism and Hinduism have their own barbarities that would translate as awkwardly into 21st Century thinking as any Islamic fatwa. Buddhists see same-sex coupling as degenerate for example, and even the Dalai Lama will not be pushed to defend the right of same-sex couples in a free-thinking society.

For even those of us that cling onto love as a saviour can be misguided, if we hold steadfast to only one definition that has at its root a dogmatic doctrine we are told not to question. When this is the case, religion becomes the eternal presence of an absence. Neither love in its truest form, or its adherents, can be said to consciously reside there. Moreover, such religious beliefs will always fail to satisfy us spiritually if we are constantly told we need to subvert our authentic selves into a moulding of medieval piety that was never much pious to begin with.

The personal "hell" of seeking heaven

It's only once we stop rejecting the idea of a truly universal love that embraces all living things simply for what they are, and not for how subservient they can be, will we be able to come out from the shadows of our past. Achieving this will not create an adversity-free utopia (like many religions promise after life has ended), rather it will bring an awareness about the real secrets to life.

For some that will mean that the negative and scary aspects of existence are every bit as needful as those we love. The Arabs have a wise saying, "Too much sunshine creates the desert." Clearly, real happiness comes in between a dialectic of sunshine AND storms. To enjoy anything, you have to be without it at times, so the sage says. The full stomach can't be filled, only the one that's not full; and the less there is in it the more pleasure there is in filling it.

For others it will be the realisation that balance comes in discovering it's not how much you have, but what you have that will bring purpose to life. If we keep wanting materials that are hollow and meaningless, they will leave us unsatisfied after time. Most men may fantasise going to bed with a glamour model, but ultimately if she doesn't love him, it will be devoid of reality. Thus getting everything you ever wanted can become an eternal punishment, if nothing you want is ever going to make you happy or give you joy.

In Bernard Shaw's 1903 four-act drama Man and Superman, he takes the same view - in his presentation of heaven and hell, hell is an eternity of parties and enjoyments and sloth, while heaven is involved in work and toil and improving reality. Similarly with women, who face the societal stereotype that there must be something wrong if they choose to stay single and focus on themselves. But why should life for a woman be all about chasing a wedding ring, instead of a healthy relationship - be that with Self or another self?

We shouldn't consciously search for more suffering, either, or decry the beauty of life, because if our existence is a lesson to greater wisdom, then we have to attend class. Being absent from life is the real crime, even if we are told that denying our existence here will reward us with heavenly afterlife. If one's eschatology features a state transcending the categories of phenomenal existence, and you conceive of an afterlife similar to that which Christians and Muslims believe, involving people in some paradise, then you're always going to be dealing with an altogether different proposition of what the purpose of life is.

But more conversely, if you presuppose an heavenly or hellish supernatural existence similar to this one (no matter how refined one's enjoyments and actions), then how can the transfigured dead be beyond good or evil? Anyone in a resurrected body will still be in the realm of interdependent opposites; and it will be as impossible for good to exist without bad in paradise as it is for up to be without down, or East without West.

Our ideas of "heaven" and "hell" are really a certain reference of the human condition that seeks a perfect "utopia society", which neither exists, and even if it did, in reality would be a terrifying nightmare. Imagine an eternal paradise with no challenges, no problems to solve, and nothing to strive for. Being in a blissful state forever would be boring to us after a time, and we would feel stuck, and want out. Of course there are those that disagree and use the analogy of the lives of royalty - their lives seem blissful from a distance, and they don't want out, so why would we if we were blessed with such eternal sunshine in our lives?

The notion of the idle rich is an old fashioned one, but under closer scrutiny, being born into a world of burden and obligation, disconnected from your species and put on a pedestal is far from being a happy state. And their lives will, in turn, be just as bad or as good as those who seemingly have access to far less materialistically than a king or queen. The happiest people, however, will be those that understand the bad will be requisite to enjoying the good. Because if without an opposite to be compared to goodness can't exist, then those who want a state made up entirely of goodness must understand that it can only be relative and not absolute.

Bringing love from out of the shadows

With complete certainty I can write that a lot of things will happen to us in this life. As season succeeds season, some will be cruel and some nice, but the funny thing is that it's always the cruel things that make us who we are today; the wise help us out, but it's the cruel that carve us out. We learn the lessons, raise our game in deference to the pain, and strive ever harder for something better. It's a spiritual balancing act between our mental, emotional and physical well-being.

And the end of March (or any time of any month) is ripe with opportunity for finding balance in our juggle to be better. The first days of January might be long gone (along with all our best resolutions), but if you were to ask astrologers they would say that now is the time to take another look, and consider new alternatives to maximise our efficiency. For those that follow astrology, the 21st of March marks the start of the spring equinox and the astrological New Year, when the sun enters the sign of Aries. For many of us, however, it's just a time to enjoy the sunshine out from under the shadow of the previous season. It's a time to banish the winter blues, as the weather warms us inside and out, and to keep striving for improvement.

At least, that's what we should do, but it's amazing how many of us still can't see so clear a truth as the preciousness of balance in the scheme of things. And true love is the great balancer in life. With that in mind, we need to get a new way of thinking about love, and a new way of looking at things in general. More than ever we need to strive to bring love from out of the shadows of dogma and limited thinking. Rather than looking at it through the current human level of understanding, we need to keep searching for wisdom with an open mind.

We have to stop imposing our human frailties, with their severe limitations and restrictions, on our aspirations, and rather accept them as the materials with which we learn about our world. If we are to advance as a species, and work towards any sort of utopia without these "flaws", then we are going to have to first embrace - rather than deny - their existence anyway. Once we do that, we are free to escape from their shadow, because they are no longer a threat to some blissful existence, rather the stepping stone towards improving our lot in life.

And the progress towards enlightenment will always be a rocky one, as the scales constantly realign to keep equilibrium. We will always have stories of the good and the bad, and of those holding sway in between. Because every swing of the scales in truth is a fresh start, a second look at a dark episode that may not be so dark after all. And wanting to maintain that balance is always the perfect opportunity to begin anew.

For as long as we exist, there is always a chance for change, which we should embrace. It should always be the speciality of our day. After all, life doesn't stand still; it's like a city that's constantly regenerating, renewing and re-inventing itself, and we should do the same. Because whatever you believe, the point is that the shift of the scales can give everyone a chance to start over - an opportunity not to be missed, if only to finally bring love shining out from beneath our own shadow.

Yours in love,

|

|